St. Petersburg, Florida is very possibly one of the most perfect destinations anywhere – a city of a delightful, walkable, liveable scale, chockablock full of fascinating things to see and do, a beautiful streetescape and waterfront, not to mention a short hop (with easy access on the trolley) to some of the prettiest beach anywhere just across the water on St. Pete Beach.

If you only have 36 hours, that is enough to hit the must-see highlights for which St. Pete is earning a deserved world-class reputation – the Dali Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg Museum of History, and the Florida Holocaust Museum – and still have time to walk about and get a feel for the emerging arts districts, such as the Central Arts District, the Waterfront Arts District, the EDGE District, and the Warehouse Arts District. (The famous Pier is now undergoing a complete reconstruction and due to reopen in 2018.)

Several of the must-see highlights of St. Petersburg are in the Waterfront Arts District: The Dali Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg Museum of History – and they are all a short walk from my hotel, a quaint bed-and-breakfast, the Cordova Inn (the renamed Pier Hotel, a renovated 1921 historic building). So on my first afternoon, after checking in, I head out to the Dali Museum.

The Dali Museum

The Dali Museum is the singular attraction that put St. Petersburg on the cultural map. Since our last visit, the entire museum has moved into a stunning new building, an architectural marvel, right on the waterfront, within the Duke Energy Center for the Arts, just across from the Mahaffey Theater.

One of the few museums devoted to a single artist, The Dali Museum has one of the most extensive collections of Salvador Dali’s art, with more than 2,000 works including 96 oil paintings, over 100 watercolors and drawings and 1,300 prints, photographs, sculptures, objets d’art, manuscripts, and an extensive archive of documents. The basis of the museum’s collection was started by Reynolds and Elena Morse, who began collecting Dali in the early 1940s, and spans Dali’s entire career (1904-1989), with key works from every moment and in every medium of his artistic activity.

I really recommend taking advantage of a free tour with a docent offered every hour on the half-hour – who can point out the interesting symbols and highlights. I was so lucky to join the tour of docent Patricia Papadopoulos who is otherwise a Registered Nurse;

The museum is one of the few in the world devoted to a single artist (and in fact, Dali built another museum for himself in his hometown in Spain). (The museum also makes an audio guide available for free, on a first-come, first-served basis.)

Seeing Dali’s early works, you appreciate his enormous talent, skill and range, and realize that could have excelled in any genre or form, but he made conscious choices to invent the fantastical imagery and techniques of surrealism. And the remarks about his background point to how he became such an individualist and innovator.

Dali (who, a docent said, was called stupid by his father and was of slight stature), became a rebel. In 1926, he was expelled from school when he was on verge of graduating because he refused to be examined by Baccalaureate committee claiming he knew more about Raphael than they did. “His defiance crushed his father’s hopes for Dali securing an art teaching position and determined Dali’s role as a rebel among artists.”

In 1929 (the same year that Dali became a surrealist), the 25-year old had a vicious falling-out with his father over his involvement with Gala, a married woman (the family were devout Catholics), that ended with Dali being banished from the family. For five years they did not speak. That tension with Dali’s father likely lasted throughout his life. Docent Patricia Papadopoulos notes that through his life he was in and out of his father’s will (when he died, Dali was on the outs).

This is a prelude to her discussion of Dali’s painting, “The Average Bureaucrat,” (1930) as a slap at his father, who was a bureaucrat. The figure appears as a kind of blob, with no ears to hear anyone’s words, small shells and pebbles in his head, without eyes or mouth, suggesting a lack of interest in the external world (there is a nose and moustache at his neck). I wonder whether it is to show contempt for his father’s conformity and distinguish himself as a someone who would challenge the status quo.

And yet, in “The Average Bureaucrat” and in other works, Dali uses sentimental images of his boyhood – painting himself as a boy holding his father’s hand.

The tension with his father increased when Dali took up with a divorced woman (his family were devoted Catholics), but clearly, as Dali uses Gala as his model and in his images – her hair so recognizable in so many of the figures and paintings and in the intimate photos by Robert Descharmes in the special exhibit, “Dali Revealed”– he was clearly completely smitten and devoted to her. Gala was his muse.

Dali is of course known for his surrealistic images and symbols – which you realize are intensely personal, like the shadow in the shape of a piano cover which harkens back to his boyhood and a neighbor who would drag a piano out to the sand for outdoor parties. But what I appreciate for the first time – because you really have to see the paintings in person – is his genius at creating double-images.

In “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea Which at 20 Meters Becomes a Portrait of Abraham Lincoln,” you see a nude woman looking out to sun through what looks like opening in tiles – tiles in the shape of a cross (he often uses images of crucifixion and martyrdom). But then you walk a distance away (20 meters or so), squint, and the entire painting becomes the bust of Abraham Lincoln (another martyrdom symbol). And if you didn’t get the message, there is also a small painting of Lincoln in a corner.

His genius in creating double images is the key to his “masterworks” – massive canvases that fill a wall and took more than a year to complete and are some of his most famous.

“The Discovery of America by Christopher of Columbus” (1958-9) is one of Dali’s Masterworks – that is, it is more than 5 ft and took longer than 1-2 years to complete.

It portrays Christopher Columbus as a young man (a striking resemblance to Jesus) – with Gala posed as the Madonna, wrapped in a flag. There are lots of Catholic images -bishop, angels, crosses – but interestingly, not a single Native American. It seems to be an unequivocal celebration of bringing Christianity to the New World.

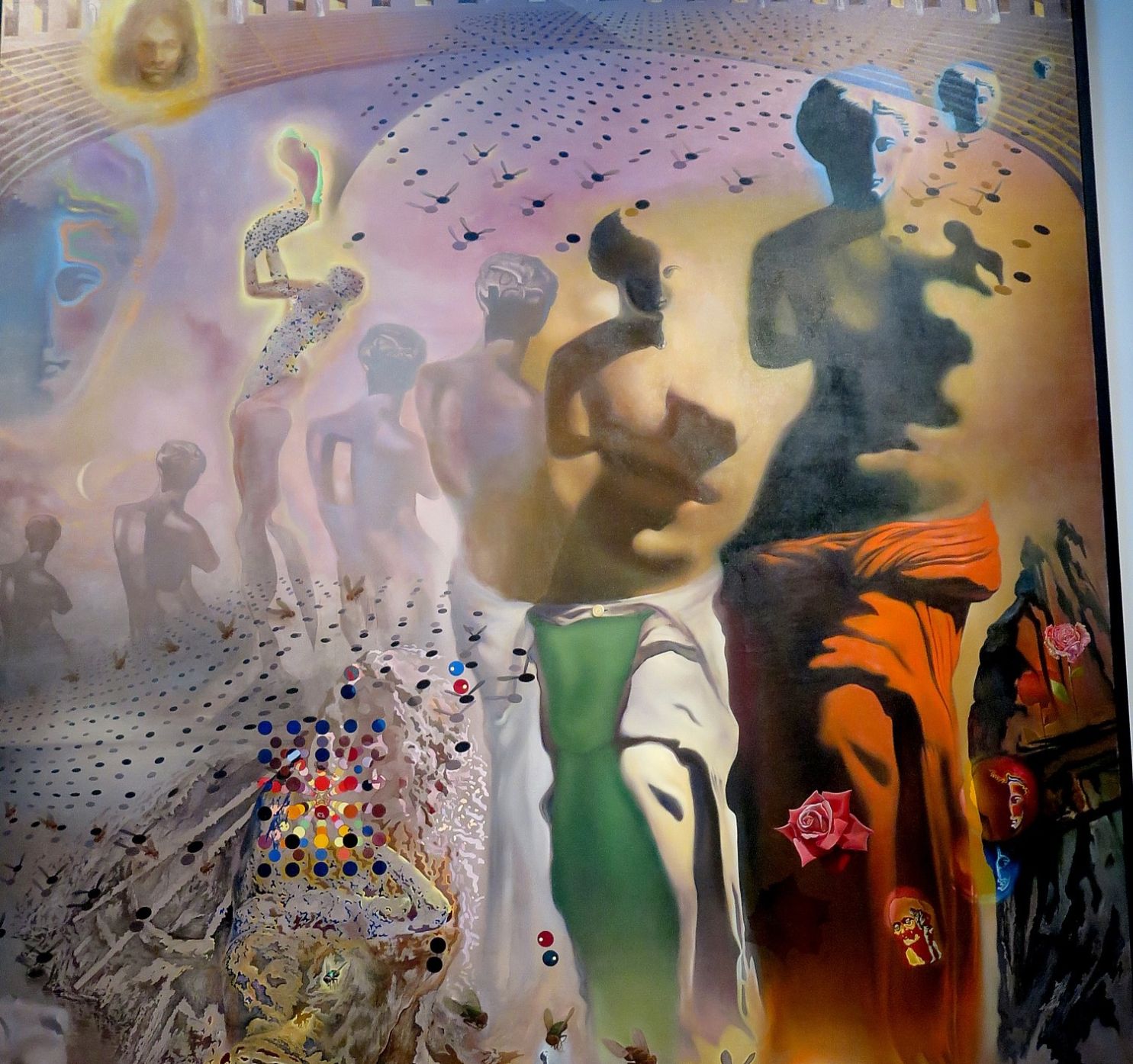

Docent Patricia Papadopoulos stops at what may be my favorite Dali in the exhibit for its complexity, its ingenious process and execution: “The Hallucinogenic Toreador,” (1969-70), another masterwork, is one of Dali’s most famous paintings (all the more interesting because of a photo of Dali watching a bullfight).

“A toreador is a bullfighter, one of the great heroes of Spanish culture. This work is arguably Dali’s most ambitious double image painting, but surprisingly, this monumental canvas has humble origins. When shopping for art supplies, Dali purchased a box of Venus-brand pencils. Staring at the Venus de Milo on the box, he glimpsed a face within the shadows. This simple experience led to one of Dali’s most complex paintings.”

At the center of the canvas, the Venus’ green skirt becomes the bullfighter’s tie. Above the tie is the white collar button of the bullfighter’s shirt. Directly above that, the shadows crossing the Venus’ stomach form the bullfighter’s chin and lips. Her left breast forms the bullfighter’s nose, and her face forms his eye. The contours of the bullfighter’s face are defined by the shadow of the Venus in the red skirt. The same red skirt is also the bullfighter’s cape hung over his shoulder. A cluster of dots and flies to the left of his tie becomes his sequined jacket.

The bull is depicted in detail, but in his eye there is a fly, and a line of flies that extend out. The bull stands over what you realize is a lagoon, with a person floating on it incongruously – homage to the fact that his town has become popular with tourists, just as bullfighting is so central to Spanish culture.

And again, there is a boy in a sailor suit, who is Dali as a boy, and an image of his wife, Gala, in the upper corner – so the piece is sentimental on many levels.

The oddly named, “Galacidalacidesoxyribonucleicacid (also known as Homage to Crick and Watson)” (1963), is a tribute to the scientists who isolated the DNA molecule. “Dali was fascinated with math, science, physics. Spirals were important to Dali” and he used the symbols frequently (which is why there is the elaborate spiral staircase which is central to the museum building). this painting has the spacemen dressed as soldiers (reminiscent of “Portrait of My Dead Brother,” homage to his brother who died in infancy, also painted in1963), who are lined up in squares, each with rifles pointed to kill each other, like mutually assured destruction of the atomic age and Cold War. Religious imagery abounds – a cloud, God reaching down, blood – an image of a village that was flooded, symbols of life-death-rebirth.

By the 1940s, Dali declared he was no longer a surrealist; after the atomic bomb, he embraces science and physics, renews his interest in Catholicism and incorporates religious imagery and by 1950, creates the term “nuclear mysticism” to describe his art.

The notes say his imagery “became more universal – moving away from surrealism’s personal imagery to shared world of science and religion.” While the science and religion are there, in my mind, the symbols remain intensely personal.

“Dali continued to work against the grain of his artistic time – late works display historical subject matter and convincing realism in an era of subjective and abstract expression…

“From his early to late periods, Dali shifted from a focus on internal and singular to the universal and from irreverence to reverence always in awe of creation and the power of art.”

Free audio guides featuring tours of the exhibit (and the permanent collection) are available on a first-come, first-serve basis, and are available to download at thedali.org/programs/apps.

Disney & Dali: Architects of the Imagination

Disney and Dali: Architects of the Imagination is a fascinating multimedia exhibition tells the story of the unlikely alliance between two of the most renowned artists of the 20th century: the brilliantly eccentric Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dali and magically inventive American animator, Walt Disney.

Presented through a multimedia wonderland of original paintings, story sketches, conceptual artwork, objects, correspondences, archival film, photographs, and audio – this comprehensive exhibition showcases two vastly different icons who were drawn to each other through their unique personalities, their enduring friendship, and their collaboration on the animated short Destino. Clips of the film play within the exhibition gallery and the full short plays throughout the day in the Museum’s theater. The exhibition’s complimentary guided audio tour is narrated by acclaimed actress Sigourney Weaver.

Both Disney and Dali embraced the ideas and technologies of their day, creating a bridge from the art of the past to the art of the future. Their legacies live on throughout today’s film, television, theater, advertising, fashion, and of course art.

“Animation pioneer Walt Disney and Surrealist Salvador Dali were two of the most revered and influential artists of 20th century – their work dissolved the boundary between reality and dreams and helped define modern culture, shaping our imagination.

“Disney & Dali were quintessential men of their era in tune with the spirit of their times – two powerful currents shaped culture of early 20th century – Sigmund Freud’s theories of psychology and profound influence of machine age.”

The juxtapositions in the exhibit are absolutely fascinating – side by side photos, big murals on opposite walls of their hometowns.

The exhibit is rich with photos, original art, movies and videos and animations that show their parallel lives. They were both about the same age (three years apart), both became leading icons of 20th century culture, both embraced science and physics in their art, and both used surrealism. Both were featured in a Museum of Modern Art Exhibit in 1936, and each was a cover on Time magazine – Dali in December 1936 and Disney in December 1937.

During World War II, the Dalis sought refuge in the US, gravitating to Hollywood, and Disney led a team of animators on a goodwill mission to South America, coming back with cultural imagery for various projects. Ultimately, this was the basis for Disney’s collaboration with Dali.

In 1941 Disney and his artists embarked on good will tour of S America that resulted in several subsequent films and a song that became the collaborative force for Disney and Dali, “Destino.”

Disney and Dali met at a party in 1945 and Disney engaged Dali to design a surrealistic animated short, using the music that Disney experienced during his goodwill trip to South America, Destino, a South American ballad. You get to see scenes from “Destino” in a theater, and the storyboards.

The exhibit includes snapshots of Dali visiting Disneyland and Disney visiting Dali in Spain in Port Ligala, plus snippets of movies, videos, old photos, cartoons, and art work all around the exhibit,

Disney in the 1950s incorporates surrealism into celebrated fantastical aspects of the world – some the same concepts of projects as Dali – “Donald in Mathmagic Land,” Alice in Wonderland (Mary Blair one of cartoonists, did concept work for Fairy Godmother and march of the cards), Sleeping Beauty, Dumbo.”

You can best appreciate Dali’s fascination with science and physics in his painting, “Still Life/Fast Moving” (1956), in which he demonstrates his knowledge of principles of physics.

To cap it off, a chance to experience Virtual Reality that puts you inside Dali’s 1935 painting, “Archeological Reminiscence of Miller’s Angelinus”. You look around the 360-degree scene which is animated (only after it do you even think about what went into animating and making 360-degree experience of a two -dimensional still image). Dali would have been thrilled.

“Dali was always exploring new ways to express his art,” said Dali Museum Marketing Director, Kathy Greif. “We are proud to give our visitors the opportunity to experience and appreciate art in new ways; advancements in virtual reality allow us to provide an almost tangible view.” Dreams of Dali was created by San Francisco based agency, Goodby Silverstein & Partners (GS&P) in partnership with The Dali. ((If you can’t visit The Dali, you can explore a 360-video of Dreams of Dali from your desktop or mobile device (go to http://thedali.org/dreams-of-dali/)

Who would have thought to juxtapose Salvador Dali with Walt Disney, but in this extraordinary exhibit, Disney and Dali: Architects of the Imagination, you appreciate how parallel their lives, how they both used symbolism, surrealism (while Dali’s use of double imagery was comparable to a filmmakers’ dissolve) – and yet, when it comes down to it, how different their outlook, and worldview. Dali’s surrealism and imagery is frightening, cynical and dark and nightmarish and intensely personal and inward looking; Disney’s surrealism was collaborative – involving the work of many artists – and his surrealism was toward the goal of creating a sense of fantasy, possibility and a dream that could be inspirational to children.

Disney & Dali: Architects of the Imagination is co-organized by The Walt Disney Family Museum and The Dali Museum, with the collaboration of the Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation in Figueres, Spain, and The Walt Disney Studios. The exhibition is guest-curated by filmmaker Ted Nicolaou and co-curated for The Dali by Peter Tush.

“Dali Revealed”

Robert Descharmes exhibit, “Dali Revealed,” is fantastic – see Dali and Gala in everyday scenes.

Over his decades of knowing and working with Dali, Descharmes accumulated 60,000 negatives of the artist, wife, friends and collectors, of which 48 were chosen for this exhibit from 80 that the Salvador Dali Museum purchased in mid-1990s. One photo shows Dali working on the Lincoln painting while staying at the St. Regis Hotel NY in 1975, another shows Reynolds & Eleanor Morse watching Dali paint, 1959.

This special exhibition includes 48 archival photographs taken by French photographer Robert Descharnes, who authored several books about Dali and collaborated together on cinematic projects over the years. Descharnes was introduced to Salvador Dali by the painter Georges Mathieu on board the S. S. America in 1950, while en route to the United States; the two remained friends until the artist’s death in 1989.

This exhibit reveals moments of Dali’s daily life, his wife Gala, their friends, and collectors. Highlights include candid moments at Dali’s home and in his studio, boating, and even at a bull fight. One particularly notable image captures the artist at work on his monumental painting “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea” in his New York residence. These photographs have not been on display for more than ten years and provide a rare glimpse into the extraordinary life of this extraordinary man.

Outside the museum, there are marvelous gardens with hedges in the shape of a maze; plaques that tell of Dali’s interest in math, a bench in the form of a melting clock, a giant Daliesque moustache, a Wishing Tree with streamers.

In 1942, the Morses visited a traveling Dali retrospective at the Cleveland Museum of Art organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and became fascinated with the artist’s work. On March 21, 1943, the Morses bought their first Dali painting-Daddy Longlegs of the Evening, Hope! (1940). This was the first of many acquisitions, which would culminate 40 years later in the preeminent collection of Dali’s work in America. On April 13, 1943, the Morses met Salvador Dali and his wife Gala in New York initiating a long, rich friendship regularly visiting the Dali’s villa in Port Lligat, Spain.

The building is itself, which opened January 11, 2011, is an attraction and a work of art, featuring 1,062 triangular-shaped glass panels – the only structure of its kind in North America, not to mention gardens that would delight Dali himself. Nicknamed the Enigma, the building provides an magnificent view of St. Petersburg’s picturesque waterfront. Inside, the central element is a spiral staircase – homage to Dali’s fascination with science and DNA and his symbolic imagery.

Designed by architect Yann Weymouth of HOK, the new building combines the rational with the fantastical: a simple rectangle with 18-inch thick hurricane-proof walls out of which erupts a large free-form geodesic glass bubble known as the “enigma”. The “enigma”, which is made up of 1,062 triangular pieces of glass, stands 75 feet at its tallest point, a twenty-first century homage to the dome that adorns Dali’s museum in Spain. Inside, the Dali houses another unique architectural feature – a helical staircase – recalling Dali’s obsession with spirals and the double helical shape of the DNA molecule.

The Dali Museum is located at One Dali Boulevard, St. Petersburg, Florida 33701., 727-823-3767, http://thedali.org/

(For more vacation planning information, Visit St. Petersburg/Clearwater: 8200 Bryan Dairy Road, Suite 200, Largo, FL 33777, 727-464-7200, 877-352-3224 www.visitstpeteclearwater.com.)

(Next: More Highlights of St. Petersburg)

__________________

© 2016 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com , www.examiner.com/eclectic-travel-in-national/karen-rubin,www.examiner.com/eclectic-traveler-in-long-island/karen-rubin, www.examiner.com/international-travel-in-national/karen-rubin and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures