George Washington’s doctor is buried in the Rose Hill cemetery at Christ Episcopal Church on Plandome Road.

So is John Hay Whitney and his wife, Betsy Cushing, residents of the Gold Coast-era Greentree estate of what is now part of the Village of North Hills. The couple shares matching headstones featuring sculptures of Egyptian-style birds locked in embrace.

So are members of the Onderdonk family, whose house is on the National Registry of Historic Places and sits untouched by the sands of time and modern design aesthetics just behind the T.G.I Friday’s on Northern Boulevard.

“There really are a lot of prominent figures buried in that cemetery,” said Norman Nemec, a local preservationist and member of the Town of North Hempstead’s Historical Society and Manhasset Preservation Society.

According to Town of North Hempstead records, the cemetery houses 1,188 internments, with the earliest burial dating back to 1802. The cemetery is still active today.

“Cemeteries are interesting because in one sense they’ve got grass and stone but they have individuals’ human histories and they have community history, and when a cemetery is more than 200 years old in a community it really goes back to a substantial amount of the founding of that community,” said Rev. David Lowry, Christ Episcopal’s rector. “It’s a very special gift, and we look at it as a gift.”

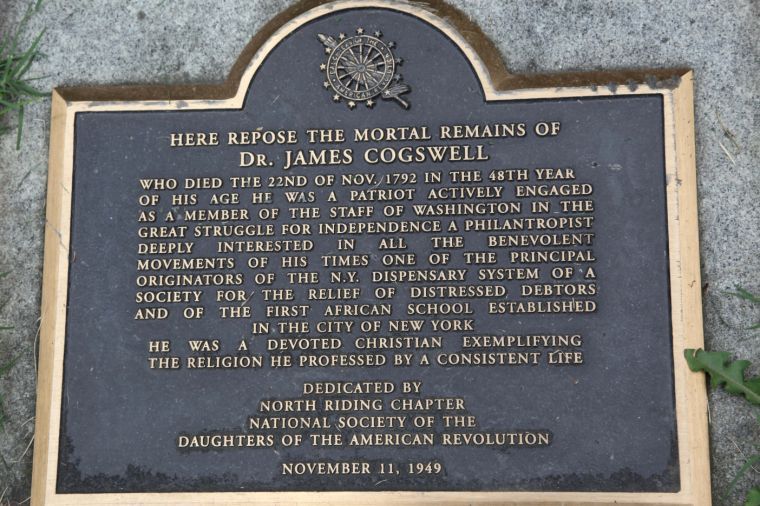

James Cogswell, a physician from the West Indies, was assigned to serve then-General George Washington and his troops during the Continental Army’s campaigns in New York City and Long Island.

Cogswell died on Nov. 22, 1792. It is unclear exactly when Cogswell was buried at Christ Episcopal. Lowry said his body may have been moved after he died.

In 1949, the north riding chapter of the National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a memorial plaque in Cogswell’s memory to accompany his headstone.

Born to the wealthy Whitney family, John Hay “Jock” Whitney was born in 1904 and went on to co-found J.H. Whitney & Co., one of the oldest venture capital firms in the United States.

Whitney was an intelligence officer during World War II and was appointed as the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom in the 1950s by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Whitney’s grandfather, John Hay, held the position 60 years earlier and served as Secretary of State under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

Whitney lived at the family’s Greentree estate with his second wife Betsy Cushing, who had previously been married to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s son John and lived on the property’s main house until her death in 1998. Whitney died in 1982.

The Onderdonks were among the earliest Dutch settlers in New York, and many in their lineage – including Horatio Gates Onderdonk, whose house was built in 1836 and put on the national registry more than 100 years later on April 16, 1980.

The Onderdonk family is buried in a large plot and monument inscribed with the family name, near the Linkletters, with whom the Onderdonks share lineage.

“In a sense, a cemetery is a living and dying book that tells the history of families that are here,” Lowry said.

Over the years, the church hosted walking tours of the cemetery, often guided by Nemec, Lowry or state Assemblywoman Michelle Schimel, when she was the North Hempstead Town Clerk.

Lowry said he doesn’t think Manhasset residents are as cognizant of the community’s history as previous generations were, as interest in the cemetery’s walking tours has dwindled in recent years.

“What’s happened, I think, for a lot of our communities, is it’s become a transitory bedroom and not really a place where people get involved on the same level as they did even 20 years ago,” Lowry said.

Nemec said a local legend suggests the cemetery was built on a native American burial ground because local tribes often chose high grounds to bury their dead and the church is located on the highest hill in Manhasset.

The Zion Episcopal Church in Douglaston, Nemec said, has a stone monument denoting the church and cemetery’s location on the burial ground of the Mattinecock tribe, which he said contributes to the legend.

“When you preserve history, you preserve how far back a community goes, and that to anyone really makes them think about the community that’s been established,” Nemec said. “It’s been around and it’s going to be around a long time. It’s just a legacy that has to continue, because once it’s gone all that’s left is the legacy.”