Two North Shore companies and a third with ties to Nassau County have proven central to the proceedings in the federal corruption trials against al state lawmakers Sheldon Silver and Dean Skelos, as pretrial court filings indicated they would.

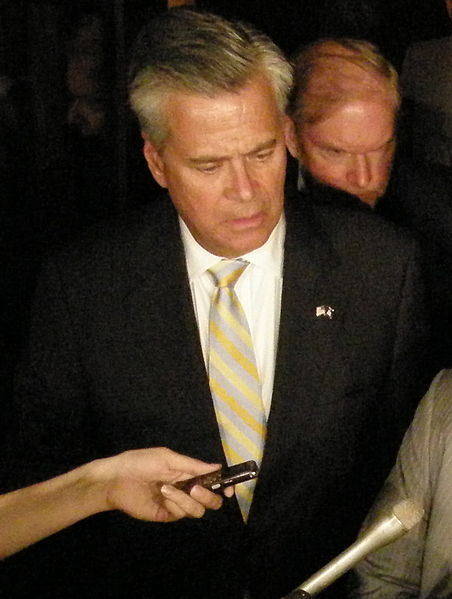

New Hyde Park-based luxury real estate developer Glenwood Management figures largely in both trials, in which state Assemblyman Silver (D-Lower Manhattan), the former speaker of the Assembly, and state Sen. Skelos (R-Rockville Centre), the former majority leader of the state Senate, are charged with using political power to procure favors and kickbacks.

Glenwood Management, which is located at 1200 Union Turnpike, was one of three companies prosecutors allege Skelos pressured into doing favors for his son Adam Skelos, who is on trial alongside his father, worth $300,000 in total.

And at Silver’s suggestion, Glenwood gave several property tax refund cases to a Manhattan law firm that had a fee-sharing agreement with the former state Assembly speaker that earned him about $700,000.

Both Skelos and Silver advocated rent control laws and real estate tax breaks Glenwood officials said the developer relies on to stay in business, news reports say.

For instance, Silver used his position to block a substance abuse treatment clinic from opening near one of the firm’s high-end downtown Manhattan buildings, according to prosecutors’ pretrial filings.

According to news reports, Glenwood officials have testified that despite discomfort with the arrangements, the firm kept them in place because of concerns about damaging its relationships with the lawmakers, who had proven themselves powerful political allies.

In 2011, a new state financial disclosure law required Goldberg & Iryami, the law firm that paid Silver a quarter of Glenwood’s tax certiorari fees, to tell its clients about all fee-sharing agreements, including the one it had with Silver.

The revelation raised red flags for Glenwood officials about the legality of the firm’s arrangement with the Goldberg firm, lobbyist Richard Runes said on the stand last week.

But, he said, the firm and its 101-year-old principal Leonard Litwin did not want to “alienate” or “make an enemy out of” him.

Brian Meara, another Glenwood lobbyist, testified that he and Runes lobbied Silver that year on tax breaks and rent control laws, Newsday reported.

In Dean Skelos’ trial, Glenwood officials testified that they were also worried about tarnishing their relationship with the former state Senate majority leader, 67, due to the political power he wielded in Albany.

Prosecutors charge Dean Skelos used his political power to get $300,000 worth of favors for his son Adam, 33.

Dean Skelos first asked Litwin and Charles Dorego, Glenwood’s top attorney, for favors in a 2010 meeting, Dorego testified.

They shrugged off the request at first, knowing it posed legal issues because of Glenwood’s interests in state legislation. “We were trying to reconcile in our minds the request … at the same time we were significantly involved with the Senate on legislative business,” Dorego said, as quoted in Newsday.

But Dorego said Skelos’ requests became more insistent and aggressive, and Glenwood eventually paid Adam Skelos $20,000 in what were called title insurance fees. The firm also connected him with Arizona-based AbTech Industries, an environmental technology company that Litwin partially owned, Newsday reported.

In 2013, prosecutors say, Adam helped AbTech win a $12 million Nassau County contract crafted around one of its products, which they allege Dean pressured county officials into awarding.

In the case of Roslyn-based malpractice insurer Physicians Reciprocal Insurance, they say, he flexed his influence over laws relating to the business located at 1800 Northern Blvd. to get Adam what turned out to be a no-show job.

Chris Curcio, the current head of PRI’s marketing department, testified that Adam often didn’t come to work and was indignant and threatening when he did show up. Curcio complained to his superior, Carl Bonomo, who had Skelos moved to another department.

Once, Curcio said as quoted in Newsday, Skelos told him, “Guys like you couldn’t shine my shoes. You’ll never amount to anything … And if you ever talk to me like that again, I’ll smash your [expletive] head in.”

PRI head Anthony Bonomo is a longtime friend of Dean Skelos, and the senator’s defense team says he gave Adam Skelos the job to help him when his father said he was struggling financially.

Dean Skelos also noted that Adam’s son has autism, something Carl Bonomo, a resident of Manhasset, cited when telling Curcio to cut Adam some “slack.”

The argument is part of a larger narrative of family loyalty that the defense is trying to weave, Newsday has reported. Rather than using his political power corruptly, Dean Skelos got favors for his son to help him in a time of need.

To win a guilty verdict, analysts say, federal prosecutors must show the lawmakers did political work in exchange for kickbacks or favors.

While no evidence has established an “explicit quid-pro-quo,” Newsday reported, U.S. District Judge Valerie Caproni told reporters last week that a case such as this can be won based on circumstantial evidence.

“There’s no requirement that people sit down and say, ‘If you pay bribes, I’ll take care of you,’” she said, as quoted in Newsday.

Representatives from Glenwood and PRI did not respond to requests for comment, nor did attorneys for Silver and Skelos.