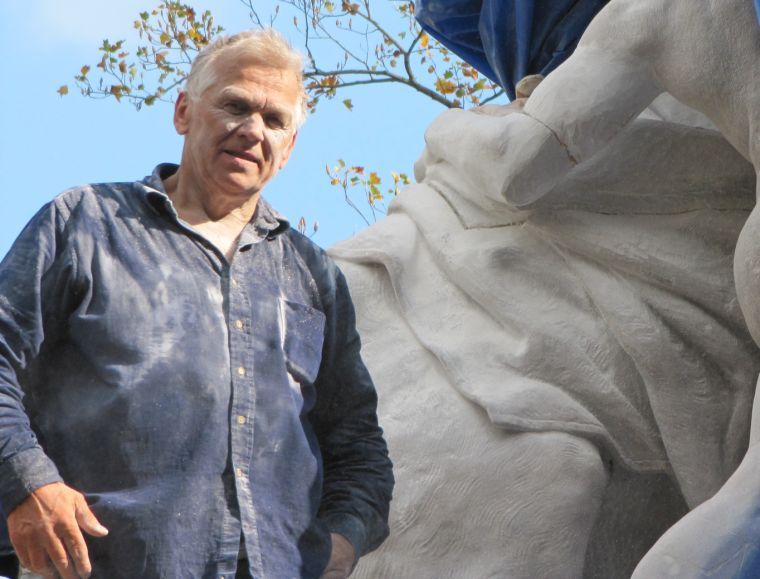

When Andre Iwanczyk found out he had been selected to lead the restoration process on the Mackay horse statue, he did his homework.

Iwanczyk learned about Clarence Mackay, the wealthy, mustached resident of Roslyn’s famous Harbor Hill estate who fell in love with the Marly horses in Paris while on a European vacation with his wife Katherine and hired artist Franz Plumelet to sculpt his very own replica.

Then Iwanczyk researched Mackay’s horses, borne from Tennessee pink marble and separated after Harbor Hill was demolished for development in 1947, yet remaining part of the Roslyn community’s consciousness ever since.

Last Saturday, Iwanczyk saw the fruit of his labor unveiled as the fully restored horse that remained on the Harbor Hill property in the backyard of a Country Estates home until it was removed in 2010 was introduced to its new home within the historic village’s Gerry Park. The unveiling ended a three-year process undertaken by the Town of North Hempstead, the Roslyn Landmark Society and North Shore Monuments of Glen Head, which housed the statue as the artist worked.

“I realized this is definitely the most important historical job I’ve worked on,” said Iwanczyk, a resident of Franklin Park, N.J. “It was thrilling and I was very focused on it and concerned about its details. It was my baby. When you do a job, it’s like peeling potatoes – you repeat the same thing. You repeat the same thing. I was always trying to do my best without stress and emotions, but on this was something that was definitely putting me on my toes.”

To complete the restoration, Iwanczyk had to redesign and connect the statue’s missing body parts – from both the horse and the tamer tending to it – and mind the details in the statue’s base – the rock and flowers over which the horse, up on hind legs, leaps.

Iwanczyk also reached out to friends and colleagues within the sculpting world to find pink Tennessee marble, tracking some down in a shop in Vermont, for as accurate a restoration as he could possibly create.

“It was really a good atmosphere and I really appreciated how much the people of Roslyn cared about the statue,” Iwanczyk said. “Some people are historical but don’t always care about restoration. [The people of Roslyn] were concerned, they were there, they were positive and helpful, really helpful. I’m very proud to be linked with the statue’s history and the community’s history.”

Iwanczyk, born and raised in Soviet-occupied Poland, said he began drawing and painting when he was two years old, though he was discouraged from going to art school as he got older.

“In Communist Poland, you really had to play the game to get a good job, even though there were plenty of them available,” Iwanczyk said. “My father discouraged me from going to art school. He said you can do art always, but learn something else.”

Iwanczyk attended the Academia of Physical Education in central Poland to become a teacher, but he began sculpting more and more as he advanced through school and even took classes at the nearby Academia of Fine Art.

Iwanczyk graduated in 1978 with the equivalent of a master’s degree and worked part-time as a gym teacher and kayak coach, focusing his spare time on his art.

In 1981, Iwanczyk vacationed in West Germany and worked for a furnishing company where he said he made more money in three months than he had in two-plus years as a teacher.

The day before his travel visa expired, Iwanczyk said marshal law had been declared in Poland and instead of going back, where his position as treasure of the Solidarity Union could have put his life in danger, he applied for asylum in Germany and then emigrated to the United States.

“I wasn’t very well-known, but I was for the [labor] movement, and my position was high enough in Poland to have gotten me punished,” Iwanczyk said. “I planned on eventually returning to Poland. I was satisfied with what I had, I was earning good money and I had my own apartment. But I waited two years and nothing changed all that much.”

Iwanczyk received his green card to the United States in 1983 and met a sculptor in the Bronx who taught him how to use modern sculpting tools on granite, rather than on furniture as he had previously been trained.

More importantly, Iwanczyk said he was taught the restoration process for a culture that was becoming increasingly interested in celebrating the past, incorporating Greek-style elements for carving hands and faces that would one day help him restore the Mackay horse statue.

“Sooner or later, this is the kind of work a sculptor will do, the restoration of broken or vandalized sculptures,” Iwanczyk said. “For serious sculptors, that’s the kind of work that’s out there these days.”